By Michelle Herbison

Charles Rose fine jewellery store owner Marcus Rose can often be found devoting many hours of his day in the rear of the office area.

“I’m often sitting at my desk right at the back of the office in Melbourne. They think I’m working out this great business strategy but I’m actually drawing,” he laughs.

Following his successful founding in Australia of family company Charles Rose jewellers and its introduction to Geelong five years ago, Marcus now combines the creative process of business with his own artistic passions.

“I devoted the first part of my life to building the business and looking after my family and that’s really my priority,” he explains.

“I’ve always been interested in painting and photography. I’ve been in the jewellery business for over 30 years but art is my personal passion.”

Marcus’ work mainly comprises large oil-on-canvas pieces painted in his studio with assistant painters, exhibited since 1994 as far as Los Angeles, Shanghai, Brisbane, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne.

While the majority of Charles Rose jewellery is handcrafted at the company’s Melbourne workrooms, multiple annual international trips are part of the job for Marcus.

“I like to combine the fun of travel with hunting for visually interesting things. I have a bit of a fascination with the built environment,” he muses.

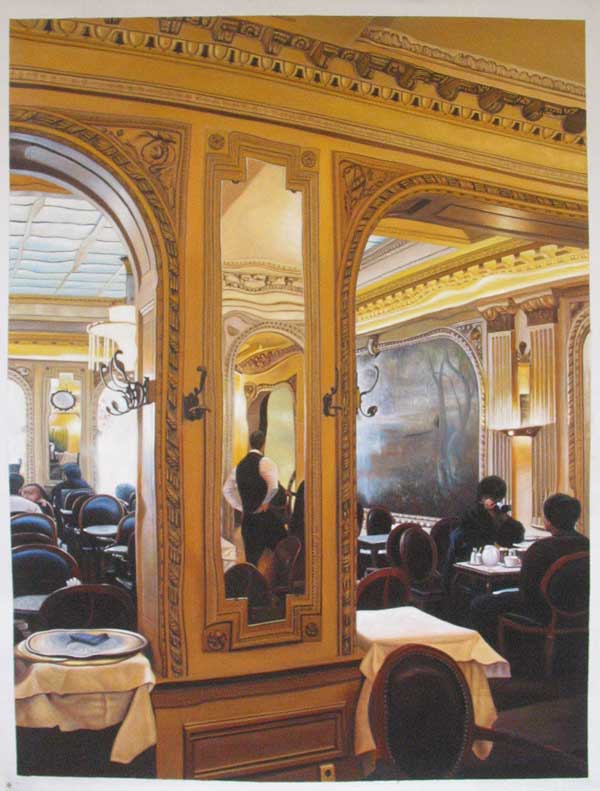

Many of Marcus’ artworks on display in an upstairs gallery at Charles Rose’s Moorabool St store are examples of his “urban landscapes”.

Travel to various corners of the globe fuelled Marcus to ponder society’s relationships with its buildings.

“When you drive into a city you know well, you feel grounded. Our architecture helps us to understand ourselves and who we are,” he says.

“Buildings represent the aesthetic of the time so it’s almost like looking back in time. But we’re ephemeral – they help us feel a degree of continuity.”

Paris, Tokyo, Shanghai and Buenos Aires are just some of the places featured in Marcus’ work as he enjoys reflecting on the differences between world location’s architecture.

“In Paris they have strict building codes but in Australia different genres of style sit side-by-side. Most Australians like to be free and easy and our architecture reflects that.

“You don’t know what you’re going to see here.”

Each “urban landscape” features Marcus’ own manipulated distortions, inspired by Hungarian-French op-artist Victor Vasarely.

In a modern treatment of the historical facades he often works with, Marcus has introduced to the real environment Vasarely’s concept of geographic lines creating optical illusions through manipulation of his photographs in Photoshop before painting.

“In producing art, you must create a visual tension. The warped bubble is a reinterpretation of the architect’s original vision,” he explains.

“We sense that buildings are permanent but the reality is they’re not permanent either. I’ve liquefied them a bit. Everything will come crumbling down.”

“Lafayette”, “Homenaje a Victor” and “Salon de The”, among others, feature warped bubbles that draw the viewer’s eye to the scene with renewed perspective.

“Exit through the garden”, featuring a striking historic copper door with a manipulated background of a grassy field, represents the need for escape often felt within cities.

“When you’re in a built environment you often feel you need to get back to nature. The doorways allow an exit to go to a new and happier place.”

“Boxcity” reaffirms a similar sentiment, illustrating the claustrophobia within a Tokyo Rippongi scene of dense, tall buildings and busy roads.

“Strikeout” features a city view from above, presenting a different perspective by looking down onto the buildings.

Marcus created this and other artworks utilising computer technology – plotting selected parts of multiple photos to create a montage.

“Paintings take a long time so computers offer a trial and error opportunity. Traditional artists and painters don’t use them enough,” he asserts.

Marcus reveals he is excited by the opportunities emerging technologies are providing for artists.

“I love that brave new world. I’ve indulged myself with off-beat graphic art and the use of technology.

“I’m lucky I don’t have to do it for a living so there’s less restriction on what I can do.”

Lately he has been experimenting with a digital drawing tablet, “like a giant iPad with an electronic pen”, which features the invaluable benefit of a tool available only in the digital world – the ‘back’ button.

“The end result is remarkably similar,” he says enthusiastically.

“But you’ve then got the question of what to do with the digital file? How is it going to get used?

“Maybe one day you’ll have a frame with a different work in there as often as you want to change it. That would fit with our instant gratification society.”

He reflects on the introduction of computer technologies to art in comparison with Andy Warhol’s famous Campbells soup tins, created in a factory-like workshop.

“He did screen-printing in the 20s which was very difficult and labour and time intensive. Now we can produce that flat, uniform graphic appearance,” Marcus reflects.

“Art is changing a lot and its focussing on the idea. But it’s about the essence of a creative act – if it can be done quickly and simply, does that make it any less worthy?”

Marcus finds the artistic process difficult to deconstruct but explains a certain set of criteria he believes good artworks require.

“A work of art needs to express an original idea, to express that idea eloquently and the craftsmanship of the person needs to be of a certain standard. If you get two out of those three, you can make a good work of art.”

Despite his successes, Marcus admits to being “eternally dissatisfied” with his artwork, always striving towards higher aims.

“If Einstein couldn’t be ‘proud’, neither can I. Fortunately I sell well but the art world is not easy.”

The gallery upstairs at his Geelong store is more of a storage place than an egocentric offering, he explains modestly.

“Once we’d developed the store, we had the other levels so I thought, ‘why not?’.”

Besides, fine jewellery and paintings seem to go hand-in-hand.

“Rings are little sculptures,” Marcus affirms with a smile.