By Natalee Kerr

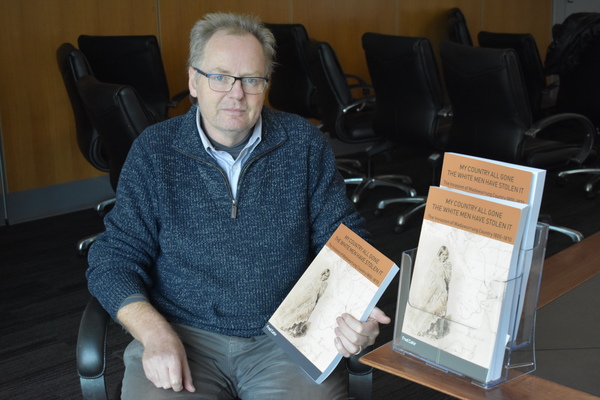

A new book recounts the early days of white settlement through the eyes of the local Wadawurrung people. And, as NATALEE KERR discovers, even author Dr Fred Cahir describes the content as “provocative”.

A Ballarat academic has wound back the clock to the 1800s with a book chronicling Aboriginal accounts of the region’s “invasion”.

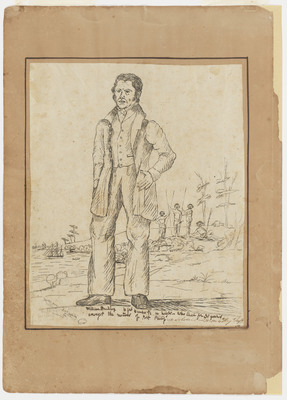

Dr Fred Cahir’s novel details the relationships and interactions between British “invaders” and the traditional owners of the Geelong and Ballarat region, the Wadawurrung people.

Dr Cahir says his inspiration for My Country All Gone – The White Men Have Stolen In came from his 30-plus years working with Aboriginal communities across Victoria and the Northern Territory.

“It really began on the Nullabor Plain in 1983 when I was cycling solo across Australia from Perth to Melbourne,” he explains says.

“I was young, dumb and blonde – a bad combination. Not surprisingly, I ran out of food and water for several days.”

After returning to Victoria, Dr Cahir began consulting Aboriginal community members and reading “history books written by white fellas”.

“The Wadawurrung community indicated to me they wanted to rewrite their version of what happened as a contrast to the white historian point of view,” he says.

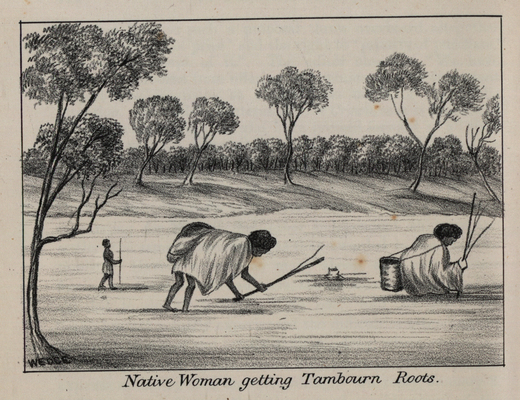

Dr Cahir worked with numerous Victorian Aboriginal groups and individuals to complete the 347-page book, which includes 40 colour illustrations.

The novel draws on three decades of archival research documenting the “invasion” of the Geelong district from 1800 to 1870, he says

The local Wadawurrung then knew the “white strangers from the sea” as the “ngamadjidj”.

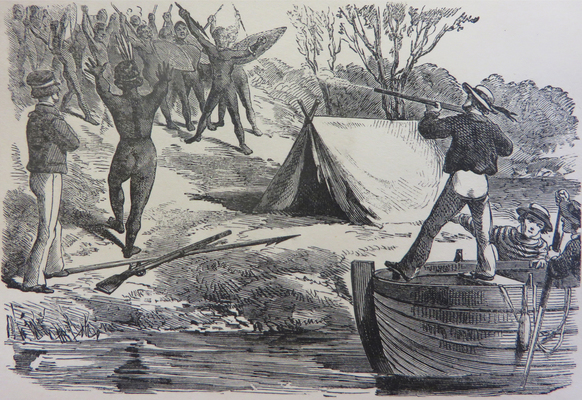

Their tales cover first contacts ranging from the arrival of the British navy through to the appearance of squatters and then gold-seekers.

As a white man, Dr Cahir thinks he could be seen as “stealing Wadawurrung history” but maintains that it was important to detail the relations between two nations.

He admits that some might find his book “provocative” and “not an easy read”.

“Any reader who sits down to read a telling of history of the region that they live and work in, which was purportedly peacefully settled, and discovers that the peaceable settlement they thought existed was in fact a ruthless and greedy conquest, will naturally be rattled,” he contends.

“It talks about the Wadawurrung’s attempts to survive the frontier war and at the same time, thrive in a new society forced upon them.

“The squatters, with their hundreds of thousands of sheep, effectively became the spearhead of the British invasion as the sheep wiped out what had been the Wadawurrung’s staple food, the root crop vegetable murnong, or yam daisy, reducing them to starvation.”

Dr Cahir’s book recounts the “great anguish’ of tghe Wadawurrung.

“There were no murnong about Geelong,” a Wadarurrung man is quoted.

“It was like Port Phillip all gone, the bulgana (cattle) and sheep eat it all.”

However, the book also details a “surprising number” of touching interactions between members of the two cultures, Dr Cahir says.

“Quite a lot of friendly and very meaningful relationships took place between the two groups.

“It’s a history that provides fine brush strokes of a wider changing frontier that was violent in nature but surprisingly had some instances of cross-cultural engagement.”

Dr Cahir describes some of the engagements as “remote islands of friendly relations in an ocean of undeclared warfare”.

“In the Geelong district, these islands took many forms including trade, work and various forms of cultural exchange and even in learning one another’s languages,” he says.

Dr Cahir believes that many of the new Australians had a “longing to belong”, which inspired some to be “indigenised”.

His book includes snippets of Wadawurrung voices documented in the records of the new Australians.

“Some of the white strangers from the sea recorded the Wadawurrung’s oral stories that predated the existence of Port Phillip Bay,” he says.

“One account relates how the Wadawurrung could at one period ‘cross, dry-foot’, from one ‘side of the bay (in the east) to Geelong (in the west)’ until a time when ‘the earth sank, and the sea rushed in through the heads, till the void places became broad and deep, as they are today’.”

Fred says the “deep-time” stories about the formation of Port Phillip Bay reflected Wadawurrung women’s expressions of grief in 1853 about the unrelenting waves of the British.

“The stranger white man came in his great swimming corong (vessel), and landed at Corayio (Corio) with his dedabul boulganas (large animals), and his anaki boulganas (little animals),” one of the women recounts in the book.

“He came with his boom-booms [double guns), his white miam-miams (tents), blankets, and tomahawks; and the dedabul ummageet (great white stranger) took away the long-inherited hunting grounds of the poor Barrabool (Wadawurrung) coolies and their children”.

Cr Cahir says anyone interested in copy of My Country All Gone – The White Men Have Stolen can email him on f.cahir@federation.edu.au for more information.