Seaweed and margarine – ingredients for a Japanese specialty dish? Not in the case of two local artists, as ELISSA FRIDAY discovers.

Pictures: Rebecca Hosking

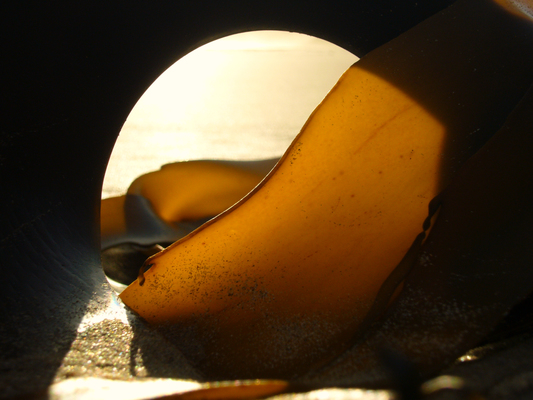

Seaweed washed-up on the sand rarely earns more than a glance – unless Janet Miller walks by.

Janet instead pays close attention to the weed, considering it as material for her next sculpture.

She came up with the novel concept years ago while watching her young son playing with seawood on a beach.

Now it’s a feature material of her art, but not just any old seaweed.

“I use seaweed that’s called bull kelp. It’s really good to use and I haven’t used anything else,” she explains.

Born in the UK, Janet was a baby when her family moved to Australia and settled at Monbulk. She attended Mater Christi and Lilydale Secondary colleges before studying at Melbourne College of Decoration then finding work behind the scenes at Channel 10.

“I was the first girl in the props and set dressing department,” she declares.

“Then I got a position in the set design department, which is where is did my apprenticeship with Chanel 10’s set design department – I was a set dresser for Prisoner’s cell block H. My first show as senior designer was with the Comedy Company, a great show to work with.”

Janet’s creative talents and enjoyment of design inform her unique seaweed sculptures, which have had a handy source of materials since Janet moved to the coast 17 years ago. She now lives with her husband and their two teenage children at Torquay.

She’s been making her unique sculptures in a “little” back garden shed for nearly two decades.

Janet prefers “really fresh” kelp in large sheets.

“We live near Fishermen’s Beach, which is where I get most of my kelp.

“When we get a dumping of kelp after an easterly I usually get pieces from near where boats come in because they don’t like it near their propellers.”

“I’m at the hands of the kelp gods as to when however much is going to come in.”

Janet uses a phone-app tide chart to time her kelp raids.

“If I don’t grab it within the six-hour window of tidal change it’s gone again,” she says.

Janet enjoys the diversity of her chosen material.

“Every piece of seaweed is totally different,” she observes.

“They vary in thickness, colour, hue and you never know what you’re going to get.”

But it’s not always so easy to work with.

“It’s tough and it has a mind of its own,” Janet laughs.

“So I mould with it while it’s still wet, then sun-dry it, but not too quickly, then I treat it with a blend of plant extracts and essential oils.”

She then monitors the completed sculpture over a few weeks to make sure the kelp has stopped shifting and has settled in its final position.

Then she considers the best ways of showing off her creations.

“I’m experimenting with light behind the sculptures now. It looks really beautiful at night time,” she says.

Janet was recently successful in Surf Coast Arts Space People’s Choice award.

“I entered for the first time last year and won with one of my female kelp bodies. Then I entered again this year and won with another kelp body, which resembles a little black dress.

“Now I’m quite inspired to enter some more exhibitions.”

Janet believes kelp has wider possibilities in the arts.

“There’s a lot more we can do with it,” she suggests.

“It’s a different medium – it’s still living a bit.”

Belmont sculptor Edward Terry Guida remembers himself as “hands-on” back in his school days at Geelong Tech.

He started out in the ’70s using clay for his art before moving on to wood and metal.

But then in the mid ’90s he enrolled in a hospitality course at The Gordon Institute of TAFE, which “sparked off a cascade of elements” that influenced Terry’s art in an unexpected direction, he explains.

“I did the course for my own interests and part of it was quantity cooking.”

It was then that he discovered the unlikely medium of … margarine.

The choice seems ironic for a son of a milk factory worker from Colac – surely butter should have been a consideration.

But Terry explains that margarine is less expensive, has a heavier oil base, and, in the case of the hospitality-grade product, a “more-solid feel”.

The inspiration for his now-locally-famous margarine sculpture was a Gordon medieval buffet function, which needed suitable decor adornments.

Terry came up with The Menu Master, based on common wizard sculptures often seen in gardens but hunched over reading a book of recipes.

He chose as his medium Pastrex, a hard margarine used in puff pastry.

The sculpture was prepared in 12 phases, taking at least six weeks to reach completion, Terry recalls.

“At one stage I was working on it until 3am,” he says.

Terry used “classic carving tools” comprising wood and wires to craft much of the figure, with his fingers employed to shape the wizard’s intricate head of hair.

“On the night it was on display at the Gordon a little child was just about to put their finger on it and I was like, ‘Oh no’,” Terry laughs, recalling The Menu Master’s debut.

Higher accolades followed for Terry’s unique artwork.

“The Menu Master won a silver award in 1995 at the annual Salon Cullinaire Australian Guild of Professional Cooks Awards, held in the Carlton Gardens, Melbourne,” he says.

“The awards included sculptures, so I was chuffed that it got recognition.”

After completing The Gordon course Terry’s access to hospitality foodstuffs was “limited”, so The Menu Master ended up his first and last sculpture in margarine.

Now he displays it in a Perspex case, positioned away from sunlight.

“It was just too hard to let go of,” Terry admits.

However, time has taken its toll, with The Menu Master undergoing repairs a “couple of times” apart from a finger that Terry allowed to drop off.

“With all things, everything isn’t forever,” Terry observes. “And as George Harrison would say, ‘All things must pass’.”

After The Menu Master, Terry moved on to experimenting with various mediums, even magnetic materials. Deakin University recently displayed some of his latest work, Conceptually Car 1950s, inspired by Ford.

He hopes his works get people thinking about art.

“Sculpture is about igniting the imagination,” Terry says.

“When people ask what it is, I ask, ‘What is it to you?’.”