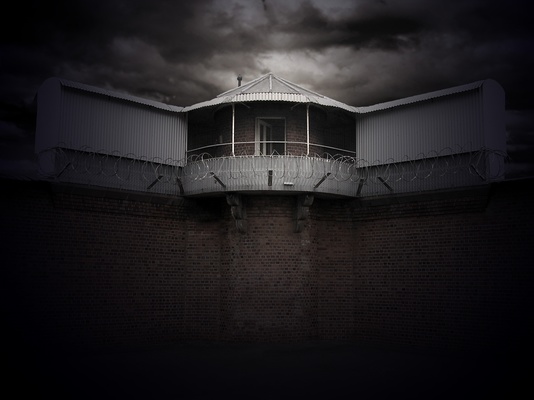

Murderous inmates, executions and daring escapes are all part of the 138-year-old historic tapestry of Geelong Gaol.

LUKE VOOGT and local historian Deb Robinson take a look the prison’s dark past.

Today’s prisons are luxurious compared to Geelong Gaol, says local historian Deb Robinson.

“Even when the gaol closed in 1991 and they went to Barwon Prison, it would have been like going to a five-star resort,” she says.

When the gaol opened in 1853, Geelong was a fraction of its size today and Victoria had declared independence from NSW just two years before.

Local prisoners rotted in four small huts in South Geelong or in hulks on Corio Bay.

NSW Clerk of Works Henry Ginn designed the gaol with 101 cells based on the Pentonville system, to keep prisoners in solitary confinement.

On the rare occasions, guards let them out, they would wear “silence masks”: white hoods with the eyes cut out.

The ghostly masks prevented the inmates from talking and learning who they were locked up with.

“You would lose your identity,” Deb says. “It sent a lot of them quite insane.”

John Gunn and John Roberts were the first Geelong prisoners executed at Gallows Flats, about 200 metres from the gaol, as 2000 people watched in 1854.

Gunn was convicted of stabbing a man in Warrnambool, while Roberts poured arsenic into a fellow servant’s cup.

“Laws at the time required executions to be public, as a deterrent,” Deb says.

When the laws changed, James Ross was the first to be executed behind the walls for the murder of Elizabeth Sayer, on 22 April 1856.

“Although, up to 70 witnesses were allowed in to ensure justice was done,” Deb says.

Authorities would execute four more men, ending with the execution of Thomas Menard or “Yankee Tom” in 1865. His remains still lie buried at the gaol.

Three wings of the gaol became a school in the 1860s, where “Matron Inch” taught 183 “street” girls, aged three to 16, sowing, cooking and cleaning.

Deb, a mother herself, says the idea of children going to school in a prison gives her the chills.

“In the newspaper of the day, there was a lot of outrage from the community.”

The school closed in 1873 after a Royal Commission in 1872 and amalgamated with a nearby industrial school.

Geelong Gaol became a hospital prison in 1877, housing some of the state’s craziest and craftiest old criminals.

In 1889 elderly inmates Christopher Farrell and Josh Clark escaped using a skeleton key and were on the run for two weeks before police caught them in Ballarat.

Henry Cutmore, the “Fire King”, was imprisoned for 12 months in May 1901 for begging and disorderly conduct.

“If you used to piss him off he would set fire to your haystack,” Deb says.

In November 1901, he jumped 6.7m from the top level and bounced off a crossbeam – leaving a dent which remains today. He died shortly after.

Local newspapers called the gaol the “Prison of the Ill”, while inmates dubbed it the “Seaside Resort”.

“Any prisoners in the state who were old, sick, debilitated or about to die – they would be sent to Geelong,” Deb says.

“We had a higher death rate than any prison in Victoria: one in 20 prisoners would die in the gaol.”

In the 1920s, the gaol was home to some of Squizzy Taylor’s most violent “Bourke Street Rats”.

Bank robber Angus Murray escaped the gaol in 1923, possibly with the help of the Rats, but would later hang in Melbourne Gaol.

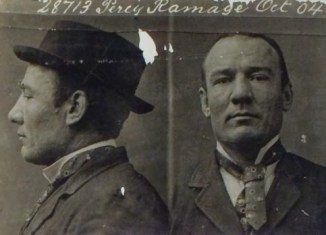

Geelong “Street Rat” Percy Ramage tried to throw a warden off the third level of the gaol.

The short-tempered Ramage was in for larceny and assault, and served time in prisons and lunatic asylums across the state due to his violent outbursts.

When the gaol closed in 1991, it was Victoria’s oldest continuously running prison, and it remains an important chapter in the state’s history, Deb says.

“It’s great reminder of how brutal the early system was.”